Hanshan 寒山 (dates of birth and death unknown), courtesy name and sobriquet also unknown, was a native of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an, Shaanxi) and lived in seclusion in the Tiantai Mountains of eastern Zhejiang for over 70 years, passing away at the age of over 100. According to modern day poet Red Pine, Han Shan was born in the ancient town of Hantan at the western edge of the Yellow River floodplain, about 300 kilometres east of Chang’an, and his family only moved to Chang’an when he was little.1 Scholars generally place his life during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), though specific details about his life are elusive due to his reclusive lifestyle and the mythical aura surrounding him.

A renowned poet-monk of the Tang Dynasty, Hanshan hailed from an aristocratic family but failed multiple attempts at the imperial examinations. Eventually, he renounced worldly pursuits, became a monk, and after the age of 30, withdrew to the Tiantai Mountains, living in seclusion and adopting the name “Hanshan” (Cold Mountain).

According to Yan Zhenfei’s Examination of Hanshan’s Life Story, supported by historical texts such as Northern History and Book of Sui, Hanshan was the son of Yang Wen, a descendant of the Sui royal family. Due to jealousy and ostracism within the imperial court, combined with the influence of Buddhist thought, he retreated to the Cold Cliffs of the Tiantai Mountains. He was known for his eccentric lifestyle, wearing a birch-bark hat, tattered clothing, and wooden clogs. He enjoyed playing with children, spoke freely and unpredictably, and was difficult for others to understand. He often visited the Guoqing Temple in Tiantai, where he befriended two monks, Fenggan and Shide. Hanshan would collect leftover temple food in bamboo tubes to sustain himself in his mountain home.

Hanshan frequently wrote poems and gathas (short Buddhist verses) on the rocks and trees of the wilderness. His poetry was straightforward, capturing the joys of mountain life and expressing Buddhist ideals of detachment, life’s wisdom, and compassion for the poor. He also criticized social norms and injustice. Han Shan’s poems focus on Buddhist and Daoist themes, with self-reflections and commentary on Tang society. These stylistic and thematic elements align with the intellectual and spiritual currents of the Tang era. His works were later compiled into the Collected Poems of Hanshan in three volumes, with 312 poems preserved in the Complete Tang Poems. In the Yuan Dynasty, his works were introduced to Korea and Japan and later translated into languages like Japanese, English, and French.

Legend has it that the Taoist that first collected Han Shan’s poetry, was a man named Xu Lingfu, who had moved to the Tiantai mountains in 815 to practice and live in seclusion as well and stayed for his remaining days. Based on several writings, we can ascertain that the two met sometime after 825 and before Xu’s death in 841.

This legendary poet, initially overlooked by society, gained increasing recognition and global dissemination in the 20th century. As one of his poems proudly declares:

“Some laugh at my poetry, [yet] my poems unite with the classical odes. No need for Zheng’s commentary, Nor Mao’s annotations to shine.”2

Han Shan is more often regarded as a spiritual figure than a historical one. He is depicted as a “laughing hermit” embodying Zen wisdom, with his poetry serving as a timeless bridge to his thought rather than a concrete record of his life.

The following are a few personal favourites that I feel capture the essence of Han Shan’s style and voice. All translations are my own.

我居山,勿人識。白雲中,常寂寂。

I reside in the mountains unaware of anyone, among the white clouds, always in solitude.

寒山深,我稱心。

純白石,勿黃金。

泉聲響,撫伯琴。

有子期,辨此音。

Deep in cold mountain, I am content.

Pure white stones are not gold.

The springs sound, and I gently pluck a qin.

If Ziqi3 were here, he’d recognize these sounds.

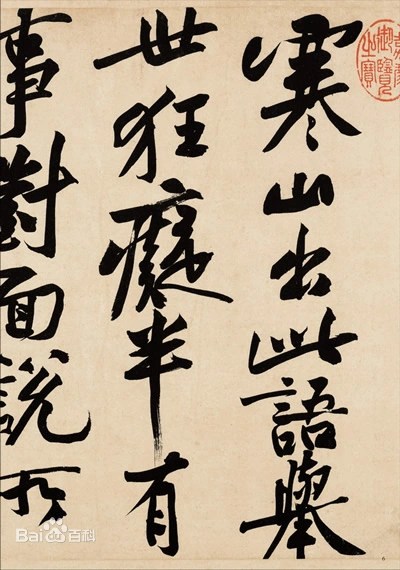

寒山子,長如是;

獨自居,不生死.

Master cold mountain, is always like this,

residing alone, free from birth or death.4

重岩我卜居,鸟道绝人迹。

庭际何所有,白云抱幽石。

住兹凡几年,屡见春冬易。

寄语钟鼎家,虚名定无益

In the layered cliffs, I chose my dwelling,

Where bird paths are cut from human presence.

What is at my courtyard edge?

White clouds embrace the shrouded stones.

I have lived here many years, observing the changes of the seasons.5

I send word to households with bells and tripods,6

Empty titles are of no benefit.

欲得安身处,寒山可长保。

微风吹幽松,近听声愈好。

下有斑白人,喃喃读黄老。

十年归不得,忘却来时道。

If you desire a place to calm your body, cold mountain can keep you protected.

A gentle breeze blows hidden pines, the closer you come, the more exceptional it sounds.

Below a grey haired man mutters [the words] he has read of Huang-Lao.7

For ten years he has not returned home, forgotten the path from which he came.

独卧重岩下, 蒸云昼不消。

室中虽暡靉, 心里绝喧嚣。

梦去游金阙, 魂归度石桥。

抛除闹我者, 历历树间瓢。

Alone I lie beneath the layered cliffs,

Steaming clouds, fail to disperse throughout the day.

Though the room is dim and misty,

My heart-mind is free from all clamor.

In dreams, I float within the imperial palace,

My ethereal soul returns, crossing the stone bridge.

I cast away things that disturb me,

Especially the gourd among the trees.

凡读我诗者, 心中须护净。

悭贪继日廉, 谄曲登时正。

驱遣除恶业, 归依受真性。

今日得佛身, 急急如律令。

All who read my poems,

Must protect and purify their heart-mind.

Let grudging and greed be purified daily,

And flattery and fawning be corrected at once.

Drive away and eliminate evil conduct,

Take refuge and receive your true nature.

Attain the Buddha’s body today—

Swiftly, swiftly, as the law commands.

家有寒山詩,

勝汝看經卷。

書放屏風上,

時時看一遍。

Having Hanshan’s poems at home Surpasses your reading of scrolls. Write them down upon a screen, And read it through from time to time.

吾心似秋月,

碧潭清皎潔。

無物堪比倫,

教我如何說。

My mind is like the autumn moon, A clear pond, pure and bright. Nothing in the world compares— How can I find the words to describe it?

- Red Pine, The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2000), 13. ↩︎

- Han Shan is referring to the Shijing (Classic of Poetry) here and is insinuating that his poetry is easier to read, hence commentaries are unnecessary. Zheng and Mao were the standard commentaries on the Shijing. ↩︎

- This is a reference to Zhong Ziqi (钟子期), a renowned Guqin (ancient Chinese seven-string plucked instrument) musician from the State of Chu during the Spring and Autumn Warring periods. Zhong Ziqi was known for his acute listening skills and deep sensitivity to music, capturing the emotions and psychological depth behind melodies. The Ziqi-style Guqin is said to have been designed in his honor, characterized by a straight and deep neck with a half-moon shape. ↩︎

- A reference to Samsāra, the cycle of birth and death or re-birth and re-death. ↩︎

- While the text literally says spring and winter, this can be translated simply as seasons. ↩︎

- This is an ancient reference to wealthy families and households. ↩︎

- Huang-Lao is an early school of Daoist thought and an important branch of Daoism that advocates active engagement with the world. It applies the philosophy of traditional reclusive Daoism to governance, aiming to achieve national prosperity and military strength. The school is named after its association with the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi) and the veneration of Laozi. Huang-Lao Daoism later became the foundation of Daoism as a religious tradition. Followers of Laozi claimed to represent the teachings of the Yellow Emperor and also revered Yi Yin and Jiang Taigong. They promoted the principles of tranquility and non-action (wu wei), avoiding interference with the people and allowing the populace to “self-transform,” thereby bringing peace and stability to the world. ↩︎