Today, I am eager to share some insights and offer a comprehensive overview of a formula that often goes overlooked but possesses remarkable effectiveness. Through the presentation of its original lines, patient characteristics, suitable conditions, and a case study, my aim is to illuminate the precise contexts, timing, and rationales behind the application of this formula.

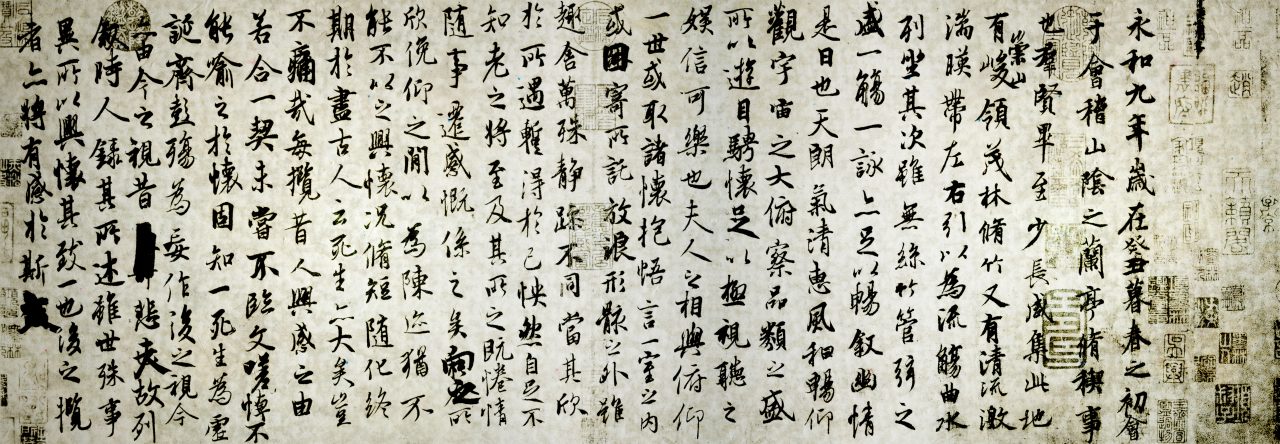

治心胸中有停痰宿水,自吐出水後,心胸間虛,氣滿不能食,消痰氣,令能食。

Jingui Yaolue 12

A treatment for collected phlegm and abiding water in the heart and chest with a vacuity of the

heart and chest, fullness of qi, and an inability to eat following the spontaneous vomiting of water.

[This formula] disperses phlegm-qi, and enables one to eat.

Composition:

Fu Ling 3 liang

Ren Shen 3 liang

Bai Zhu 3 liang

Zhi Shi 2 liang

Ju Pi 2.5 liang

Sheng Jiang 4 liang

Formula Presentation:

- Stifling sensation in the chest

- Abdominal distention

- Vomiting of watery mucus

- The sound of splashing water in the stomach

- Poor appetite.

Patient Characteristics:

Emaciation: gaunt appearance, a pale and sallow complexion that lacks luster, dusky pale lips and tongue or a slight degree of superficial facial edema.

Digestive upset: lack of appetite, a loss of hunger sensation or abdominal fullness and discomfort after eating, frequent belching, a bitter taste in the mouth, vomiting of fluids, acid reflux, and heartburn. The tongue coating will be thick and could also be white and/or greasy.

Stoppage of fluids in the stomach: a soft abdominal wall that lacks resistance or one that although tight has a sense of nothing underneath; this is most often observed along with splash sounds in the stomach and accumulations of qi in the upper abdomen.

Suitable Conditions

Digestive diseases including gastric diseases such as gastric prolapse, gastric atony, chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, gastric injury from NSAIDs, and anorexia; intestinal diseases such as pediatric diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, habitual constipation; chronic pancreatitis, and post-operative abdominal pain.

Other disorders including cardiac insufficiency, breast lobular hyperplasia, fibroadenomas of the breast, uterine prolapse, hypotension, motion sickness, eczema, and chilblains.

Commentary by Huang Huang

Great formula for gastric motility and is able to speed up gastric emptying and eliminate fluids retained in the stomach. In this way it restores the appetite. Patients are usually thin and weak with flat abdomens, abdominal walls that lack elasticity, and prominent splash sounds in the stomach. If these weak patients are mistakenly given enriching and tonifying substances, it can result in ascending fire with them feeling upset, irritable, and restless.

Patients typically experience abdominal distention right after eating and complain of a strong sense of pressure in the chest and abdomen that is slightly relieved by belching. They will vomit up fluids or froth and do not feel hungry. This discomfort in the stomach often leads them to be depressed and anxious and have insomnia, palpitations, lightheadedness, and headache. This can be accompanied by a bitter taste in the mouth and a sense of something being stuck in the throat.

While these patients have a rather thick tongue coating, the tongue body itself is not necessarily swollen and may in fact be thin and small. Usually it tends to be dusky.

Dr. Huang usually increases the dosages of zhǐ shí and chén pí up to 30g each.

Case Study

Li, 39-year-old female, 160cm/48kg.

Initial consultation on January 6, 2017.

History: Two years ago, after giving birth, the patient suffered from depression that manifested as a stifling sensation in the chest, fluttering in the chest, irritability and uneasiness, and a poor appetite. Recently she had experienced epigastric distention and pain that was more pronounced after eating, with occasional acid reflux. Her stools were typically loose, and she was frequently dizzy, had a hard time falling asleep and occasionally had difficulty getting to sleep throughout the night. In addition, she had vitreous opacity and dry eye disease.

Signs: Thin build, sallow complexion with dark spots, splash sounds in the stomach, periumbilical pulsations, red inner eyelids (checked by drawing down the lower lid), a thick-greasy tongue coating, and a weak pulse, which was forceless hardon heavy pressure. Her blood pressure tended to be low.

Prescription: fú líng 40g dǎng shēn 15g, bái zhú 20g, zhǐ ké 20g, chén pí 20g, gān jiāng 5g, guì zhī 15g, zhì gān cǎo) 5g; 10 packets.

Second consultation on February 14, 2017: After taking the formula, her abdominal distention was reduced and her sleep improved. Her tongue coating was still thin, and her facial spots were less dark. The same formula was given, to be taken every other day.