Case of Obstructive Jaundice

The patient is a 68-year-old male, 165 cm tall, and weighs 61 kg. Initial consultation on August 19, 2019.

Medical History: Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, splenomegaly. In July of this year, he underwent a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure, which improved ascites, but his bilirubin levels continued to rise.

Examination (August 9, 2019): Total bilirubin 216.3 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 195.5 μmol/L, indirect bilirubin 20.8 μmol/L. The patient reported poor mental state, fatigue, moderate appetite, urinating 2 liters per day, yellow urine, poor taste, and swollen feet after walking a lot. He did not experience obvious thirst. His past medical history includes hypertension, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema.

Physical Examination: The patient appeared fatigued, spoke slowly, had yellow-orange skin, yellow sclera, a soft abdomen without resistance, a thick yellow tongue coating with a red tongue, and mild edema in the lower limbs.

Prescription:

- Yīnchénhāo 50g, guìzhī 15g, báizhú 30g, fúlíng 30g, zéxiè 30g, zhūlíng 30g, 10 doses.

- Yīnchénhāo 30g, zhīzǐ 15g, zhì dàhuáng 5g, 10 doses.

These two prescriptions were alternated every other day.

Follow-up (September 23, 2019): After treatment, his taste sensation improved, and bilirubin levels decreased. A lab check on September 22, 2019, showed total bilirubin at 88.9 μmol/L and direct bilirubin at 76.5 μmol/L.

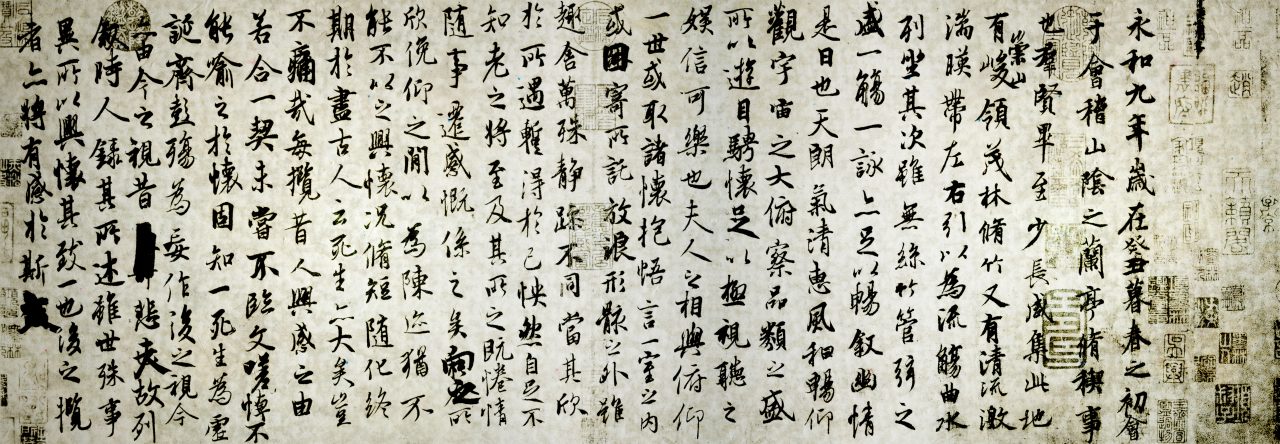

Note: The two formulas used in this case are both classical formulas for reducing jaundice. Yīnchénhāo Tāng is effective for bright-colored jaundice, while Yīnchén Wǔ Líng Sǎn is used for jaundice accompanied by ascites and edema. The method of alternating the two formulas was adopted out of respect for ancient usage in classical formulas. According to the Shānghán lùn and Jīnguì yàolüè, no formula combines zhīzǐ with báizhú, fúlíng, and guìzhī, nor does it combine dàhuáng with báizhú. Therefore, mixing them into one formula and decocting together might not be appropriate. To be cautious, they were decocted and taken separately.

Case of Rectal Cancer

Ms. Jin, a 36-year-old woman, measuring 150 cm in height and weighing 44 kg, was first seen on April 11, 2018. She had been diagnosed with rectal cancer for seven months and had not undergone surgery. She had received eight rounds of chemotherapy and 25 sessions of radiotherapy. A CT scan from March 9, 2018, showed that the rectal cancer, located about 8 cm from the anus, had shrunk compared to previous scans, while the small retroperitoneal lymph nodes remained unchanged.

At the time of consultation, she experienced dull abdominal pain, bloating after eating, and abdominal distension before defecation. Her bowel movements were sticky and adhered to the toilet bowl, occurring once or twice per day, with difficulty passing stool smoothly. She also reported a sensation of body heat, poor sleep, and frequent dreaming.

On physical examination, she appeared thin, with bright and alert eyes. Her skin was yellowish-black but had an oily sheen, and there were pigmentation spots on her face. Her tongue was thin with a yellow, greasy coating, and the sublingual veins were engorged. Although there was no tenderness in the abdomen, it felt hot to the touch. Her navel temperature was 38.9°C, while her forehead temperature was 37.1°C. Her pulse was slippery and rapid at 120 beats per minute.

She was prescribed a formula consisting of bàitóuwēng 10g, huánglián 5g, huángbǎi 10g, qínpí 10g, huángqín 15g, báisháo 15g, gāncǎo 10g, and hóngzǎo 30g, to be taken in 15 doses.

At her follow-up visit on May 8, 2018, she reported that the abdominal pain had disappeared after taking the medicine. Her complexion had become fairer and more radiant. Sticky stool, excessive hunger, and night sweats had resolved, and the heat in her palms and soles had decreased. She felt comfortable overall, and her navel temperature had dropped to 36.6°C. The same formula was prescribed for another 15 doses, to be taken every other day.

At her third consultation on May 15, 2018, a test report from May 11 confirmed that the tumor was no longer present. Her stool had returned to normal in consistency and color, her navel temperature was 37.8°C, and her appetite was good with no significant discomfort. The same prescription was continued for another 15 doses.

This case was treated with a combination of Bàitóuwēng tāng and Huángqín Tāng, two classical formulas used to stop dysentery. These formulas are effective for conditions such as cervical cancer, rectal cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer, and bladder cancer in patients presenting with symptoms such as foul-smelling, sticky, and incomplete bowel movements with tenesmus, anal heaviness, and a burning sensation, or with foul-smelling vaginal discharge or thick uterine bleeding.

This formula, being bitter and cold in nature, is particularly suited for individuals with a heat-type constitution. Such patients often have red lips that appear as if they are wearing lipstick, a red tongue with prickles, an irritable temperament, a sensation of heat in the body and limbs, a burning sensation on the skin, and an abdomen that feels hot to the touch, with an especially high temperature at the navel.

The presence of internal heat is a key indication for huángqín. The Jīnguì yàolüè describes Sān Wù Huángqín Tāng as treating postpartum women who develop heat and agitation in the limbs due to exposure to wind. The Qifang Leibian records that boiling huángqín in a decoction can treat extreme summer heat symptoms, where the head feels swollen like a large bucket and the body burns like fire. The elevated navel temperature mentioned in this case also warrants further study, as the Leizheng Huoren Shu states that in cases of concurrent heat diarrhea, the area below the navel is always warm.