From ‘Essential Points on Clinical Patterns in the Shanghan Lun’. [刘渡舟-伤寒论临证指要]

水气病脉证并治

Water Qi Disease, Pulses, Patterns, and Treatment.

[The following are lines found within the Jingui Yaolue Water Qi chapter]

《金匮•水气病脉证篇》:“少阴脉,紧而沉,紧则为痛,沉则为水,小便即难。

“[When] the shaoyin pulse is tight and deep, tight signifies that there is pain, while deep signifies that there is water, [with] difficult urination.” [JGYL 14.9]

脉得诸沉者,当责有水,身体肿重”。

“[When] all pulses are deep, this is the responsibility of water, and manifests with generalized swelling and heaviness.” [JGYL 14.10]

“跌阳脉当伏,今反紧,本自有寒疝瘕,腹中痛。医反下之,下之则胸满短气。

“The instep yang pulse should be hidden, but conversely now it is tight, this is because there is cold at the root with mounting conglomerations and abdominal pain. If a physician incorrectly purges, this will result in chest fullness and shortness of breath.” [JGYL 14.6]

跌阳脉当伏,今反数,本自有热,消谷,小便数,今反不利,此欲作水”。

“The instep yang pulse should be hidden, but conversely now it is rapid, this is because there is heat at the root, causing dispersion of grain and frequent urination. If the urination is inhibited, this means water is soon to rise.” [JGYL 14.7]

“寸口脉弦而紧,弦则卫气不行,即恶寒,水不沾流,走于肠间”。

“[When] the cun kou pulse is wiry and tight, wiry signifies that the defensive [qi] is not moving, which manifests with aversion to cold, and water that does not moisten and flow, [but is] running into the intestines.” [JGYL 14.9]

又“夫水病人,目下有卧蚕,面目鲜泽,脉伏其人消渴,病水腹大,小便不利,其脉沉绝者,有水,可下之。

“A patient with water disease has sleeping silkworms below the eyes, a bright sheen in the face and eyes, a deep pulse, and dispersion thirst. [If] water disease manifests with an enlarged abdomen, inhibited urination, and a deep and expiring pulse, [this indicates] water, which can be purged.” [JGYL 14.11]

又“水病脉出者死。”

“In water disease, [when] the pulse bursts out, [the patient] will die.” [JGYL 14.10]

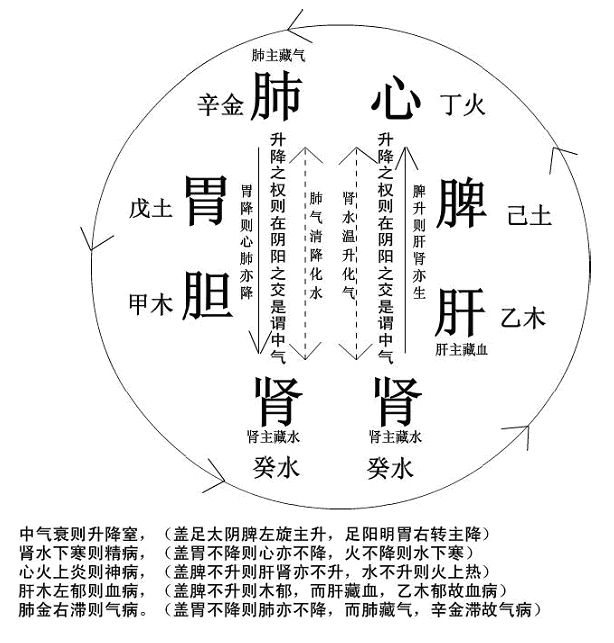

以上援引《金匮》对水肿病的脉诊、色诊、问诊以及预后不良之诊,对指导临床意义非凡。 水气病可分为四种类型:风水、皮水、正水、石水。至于五胜之水气,可列人正水,石水之范畴。 大肿精那实而正不虚的有三种洽疗友法,即发汗,利小便与攻下之法。这就是《内经》说的“开鬼门,洁净府”的治疗原则。

The above quotes from the “Jingui” regarding the pulse diagnosis, color diagnosis, questioning, and the prognosis of edema have extraordinary significance in guiding clinical practice. Water qi can be classified into four types: wind-water, skin-water, true-water, and stone-water. As for five viscera water qi, they fall into the categories of true-water and stone-water. There are three effective therapeutic methods for excess and non-deficient major swelling, namely sweat effusing, urination disinhibiting, and offensive purging. This corresponds to the treatment principle mentioned in the “Neijing” as “opening the ghost gate and cleansing the mansion.”

一、风水

风水由于风邪侵袭肌表,故脉来而浮;若卫气虚不能固表,则脉浮软而见汗出恶风之证;荣卫之行涩,水道不利,而水湿滞于分肉,则身重而懒于活动。

【治法】疏风益卫,健脾利湿

【方药】防己黄芪汤

防已一两,甘草半两(炙),白术七钱半,黄芪一两(去芦)

上倒麻豆大、每抄五钱匕、生姜四片、大枣一枚、水盏半、煎八分,去渣温服,良久再服。喘者加麻黄半两,胃中不和者加芍药三分,气上冲者加桂枝三分;下有陈寒者加细辛三分。服后当如虫行皮中,从腰下如冰,后坐被上,又以一被绕腰下,温令微汗,瘥。

I. Wind-Water

Wind-water occurs due to the invasion of wind pathogens in the fleshy exterior, resulting in a floating pulse. If defensive qi is deficient and cannot secure the exterior, the pulse becomes floating and soft, accompanied by symptoms such as sweating and aversion to wind. The circulation of nutrient and defensive qi becomes obstructed, leading to water stagnation in the muscles, causing heaviness and reluctance to move.

[Treatment Method] Course wind, boost the defensive [qi], strengthen the spleen, and disinhibit dampness.

[Prescription] Fangji Huangqi Tang

Fangji (1-2 liang), Gancao (half liang, roasted), Baizhu (seven and a half qian), Huangqi (1 liang, husked)

Cut the above [ingredients] to the size of hemp seeds. Scoop up five qian-spoonfuls per dose [and add this with] four slices of shengjiang and one dazao to a cup and-a-half of water. Boil this down to eight tenths and remove the dregs. Take warm and wait a while before taking more. For panting, use an additional half liang of mahuang. For disharmony in the stomach, add three fen of shaoyao. For upward surging qi, add three fen of guizhi. For old cold in the lower body, add three fen of xixin. After taking [the formula, the patient should feel a sensation] like bugs crawling in the skin and icy coldness from the waist down. [Have the patient] sit on a bedcover and wrap another bedcover around them below the waist, to make them warm enough to cause a slight sweat. This will bring about recovery.

如果风水而一身悉肿,脉浮,恶风,反映了风邪袭于肌表,肺气之治节不利,决渎失司,水溢皮肤,故一身悉肿。风邪客表则恶风,气血向外抗邪故脉浮;风性疏泄可见汗出;汗出则阳气得泄,故身无大热。此证治以越婢汤,宣肺以利小便,清热以散风邪。

If wind-water manifests in generalized swelling with a floating pulse and aversion to wind, it indicates that wind pathogens have attacked the fleshy exterior. [Here] lung qi is hindered, leading to the loss of control [of water] with water overflowing into the skin, which results in generalized swelling. When wind pathogens settle in the exterior, there is aversion to wind, and [because] qi and blood move towards the surface to contend with the pathogen, the pulse becomes floating. Sweating is a manifestation of the free coursing nature of wind. [With] sweating, yang qi is discharged, therefore there is no major heat in the body. For the treatment of this condition, Yuebi Tang is used to diffuse the lungs, promote urination, and clear heat in order to scatter wind pathogens.

越婢汤方

麻黄六两,石膏半斤,生姜三两,甘草二两,大枣十五. 校以水六升,先煮麻黄去上沫,内诸药,煮取三升、分温三服。恶风者加附子一枚,炮。

方中麻黄宣肺以利水,石膏清解郁热以肃肺气之下降;

甘草补脾以扶正;姜、枣调和荣卫以行阴阳。

Yuè Bì Tāng

Mahuang 6 liang, Shigao 1/2 jin, Shengjiang 3 liang, Gancao 2 liang, Dazao 15 pieces.

In 6 sheng of water, first boil the mahuang and remove the foam that rises to the top. Add the remaining ingredients and boil until three sheng remain. Separate and take warm in three doses. With aversion to wind, add one piece of blast fried fuzi.

Within the formula mahuang diffuses the lungs and disinhibits water. Shigao clears and resolves depressed heat, addressing the downbearing of lung qi.

Gancao supplements the spleen in order to support the right [qi]. Shengjiang and dazao harmonize the nutritive and defense in order to move Yin and Yang.

以上两证,虽同为“风水”而有虚实之分(亦如桂枝汤和麻黄汤虚实之分)。审其虚者,则用防己黄芪汤,一定抓住“身重汗出恶风”的主证;审其实者,则用越婢汤,一定抓住“脉浮、恶风、身肿不渴”的主证。

The two conditions above, though both involving “wind-water,” are differentiated based on deficiency and excess (similar to the differentiation between Guizhi Tang and Mahuang Tang). For deficiency, use Fangji Huangqi Tang to address the main symptoms of “body heaviness, sweating and aversion to wind.” For excess, use Yuèbì Tāng, focusing on the main symptoms of “floating pulse, aversion to wind, body swelling, and no thirst.”

对水肿发作时需要察其部位而治之。才能达到“因势利导”使水邪乃服。仲景曰:“诸有水者,腰以下肿,当利小便;腰以上肿,当发汗乃愈。”凡腰以上肿,多因风寒湿邪,侵于肌表,闭郁肺气,水湿停留而成。故治宜宣通肺气,开发毛窍,使在外之水从汗液排出;腰以下肿,有虚有实;虚者为阳气不足,不能化气行水而使水邪停居于下;实者为水湿之邪停留于下而为水肿,但其人正气不虚、脉沉而有力,兼见小便不利,以及腹部胀满证。

When treating edema, it’s crucial to observe its location and treat accordingly. [When one] is able to “guide ones actions according to the circumstances”, [then] water pathogens can be addressed. Zhang Zhongjing said;

“In all cases of water, with swelling below the waist, one must disinhibit urination; for those with swelling above the waist, one must effuse sweat in order to resolve.”

All swelling above the waist is often caused by wind-cold-damp, which invade the fleshy exterior and block and depress lung qi, [which results in] the settling of water-damp. Therefore, suitable treatment is to diffuse and free lung qi, open and effuse the orifices, and cause the discharge of water on the surface though the sweat. For swelling below the waist, there is both deficiency and excess. Deficiency is due to insufficiency of yang qi, which is unable to transform qi and move water, which leads to the stoppage and residing of water pathogens in the lower body. Excess is the result of water-damp pathogens that have stopped and settled in the lower body with water swelling. Although the patients right qi is not deficient, the pulse is deep yet strong, and is accompanied by inhibited urination as well as abdominal distention and fullness signs.

腰以上肿,发汗当用越婢加术汤(即越婢汤加白术四两);腰以下肿,而阳虚气寒,小便不利当用真武汤;脉沉有力而小便不利者,当用牡蛎泽泻散(牡蛎、泽泻、瓜蒌根、蜀漆、葶苈子、商陆根、海藻各等分,同捣,下筛散),更于白中治之,白饮和服方寸匕,日三服。小便利,止后服。

For swelling above the waist, [one must] effuse sweat by using Yuebi Jiazhu Tang [Yuebi Tang with 4 liang of Baizhu]. For swelling below the waist, due to yang deficiency qi cold with inhibited urination, use Zhenwu Tang. When the pulse is deep and strong and the urination is inhibited, use Muli Zexie San [equal parts muli, zexie, guslougen, shuqi, tinglizi, shanglugen, and haizao pounded and sieved into a powder]. Work [the powder] in a mortar to blend with a white [rice] cool decoction. Take a square inch spoonful three times a day. [If] urination is uninhibited cease taking [the decoction].

水之去路有二:在表者发汗,在里者渗利,因势利导,使水气得去而愈。但临床所见,也有腰以上肿,而内渗于里;腰以下肿,而外溢于表,以致肺气不宣,肾气不化,大气不转。如此则可变通其治:如以发汗去其表邪,又要兼用滲利,务使在里之水可以尽去;腰以下肿,既要渗利,又应“提壶揭盖”开其肺气,使上窍通而下窍利,则水邪方能尽去。发汗与利小便治水两大法宝,此外对于正虚者又有温阳化气,健脾运水、扶正祛邪、益气固表等法。应变通选用而不拘于一格。

There are two roads for the elimination of water: through the exterior by means of sweat effusion, and through the interior by means of percolation and disinhibiting. By guiding one’s actions according to circumstances, water qi can be expelled resulting in resolution [of the condition]. However, in clinic one may see [cases] with swelling above the waist and inward percolation to the interior; swelling below the waist and outward seepage into the exterior resulting in lung qi not diffusing, kidney qi not transforming and major qi not shifting.

In such cases, flexibility is needed for treatment, such as effusing sweat to eliminate the exterior pathogen, while at the same time using a percolating and disinhibiting [method] to ensure that water in the interior can be completely expelled. [For] swelling below the waist, we already want to percolate and disinhibit, and also apply the “lift the pot and remove the lid” [method] to open lung qi, which causes the upper orifices to be free and the lower orifices to be disinhibited, resulting in the complete expulsion of water pathogens.

Sweat effusion and disinhibiting urination are two magic weapons for treating water [diseases]. In addition, for those with deficiency patterns, there is the method of warming yang and transforming qi, strengthening the spleen and moving water, supporting the right and dispelling pathogens, and boosting qi to secure the exterior, among other techniques. One should be flexible in choosing and applying these methods, without adhering strictly to a single approach.