Wáng Wéi 王维 (693 or 694 or 701 – 761), courtesy name Mójí 摩诘, also known as Mójí Jūshì 摩诘居士, was originally from Hédōng Púzhōu 河东蒲州 (modern Yongji, Shanxi). He later moved to Jīngzhào Lántián 京兆蓝田 (modern Lantian, Shaanxi), and his ancestral home was Qíxiàn 祁县 in Shanxi. He was a poet and painter of the Tang dynasty.

He came from the Hedong branch of the Tàiyuán Wángshì 太原王氏, known specifically as the Hédōng Wángshì 河东王氏. At nineteen, he traveled to Jingzhao prefecture to sit for the examinations and won first place. At twenty-one, he passed the jìnshì 进士 examination. Over the years, he served as Yòu Shíyí 右拾遗 (Right Remonstrator), Jiǎnchá Yùshǐ 监察御史 (Censor), and Héxī Jiédùshǐ Pànguān 河西节度使判官 (Assistant to the Military Commissioner of Héxī).

During Emperor Xuánzōng’s Tiānbǎo era, he was appointed Lìbù Lángzhōng 吏部郎中 (Director in the Ministry of Personnel) and Gěishìzhōng 给事中 (Palace Aide). When Ān Lùshān 安禄山 captured Cháng’ān 长安, Wáng Wéi was forced to accept an official position under the rebel regime. After Cháng’ān was retaken, he was demoted to Tàizǐ Zhōngyǔn 太子中允 (Assistant to the Heir Apparent), but later rose to Shàngshū Yòuchéng 尚书右丞 (Vice Minister of the Ministry of Works). He died in the second year of the Shàngyuán 上元 era (761), in the seventh month, at the age of sixty-one.

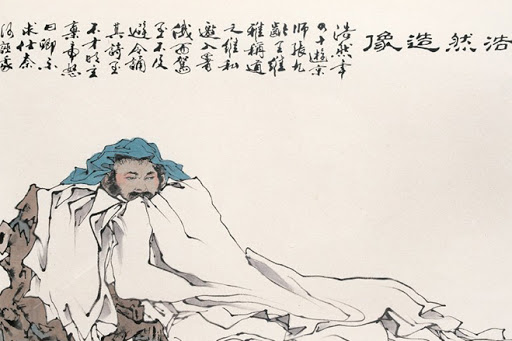

Wáng Wéi not only practiced Chán 禅 Buddhism and studied Daoist teachings (Zhuāngxué 庄学, Xìndào 信道), but also excelled in poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music. His poetic fame was especially prominent during the Kāiyuán 开元 and Tiānbǎo 天宝 eras, and he was particularly skilled in five-character verse (wǔyán 五言).

Many of his poems describe landscapes and pastoral life; together with Mèng Hàorán 孟浩然, he was known as “Wáng–Mèng 王孟” and was honored with the title “Poet-Buddha” (Shīfó 诗佛). His painting, especially his landscape style, reached great heights, and later generations regarded him as the founder of the Southern School of landscape painting (Nánzōng shānshuǐhuà zhī zǔ 南宗山水画之祖).

Sū Shì 苏轼 said of him:

“Taste Mojie’s poems and there are paintings within them; view Mojie’s paintings and there is poetry within them.”

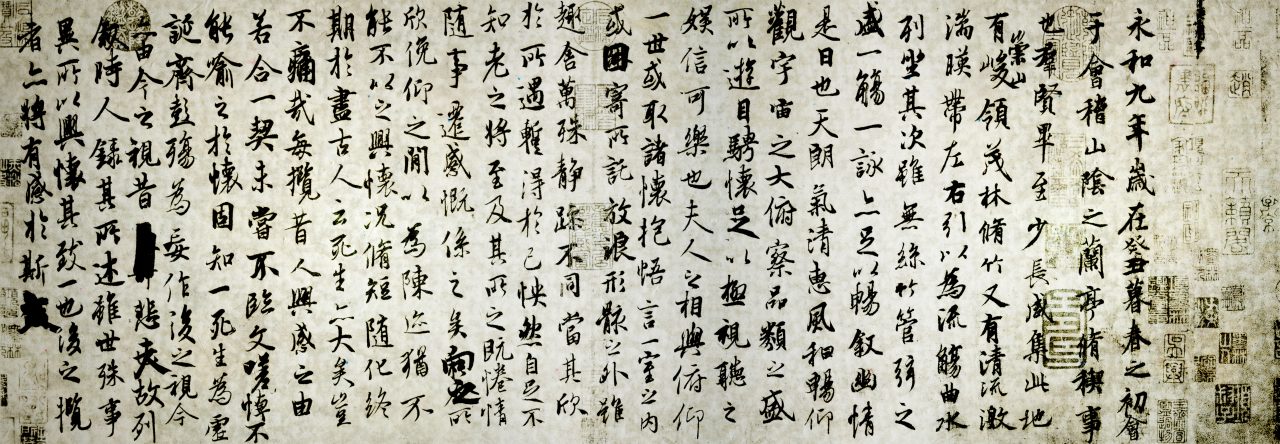

More than 400 of his poems survive today. Representative works include “Xiāngsī 相思” (Longing) and “Shānjū Qiūmíng 山居秋暝” (Autumn Evening in the Mountains). His extant writings include Wáng Yòuchéng Jí 《王右丞集》 and Huàxué Mìjué 《画学秘诀》.

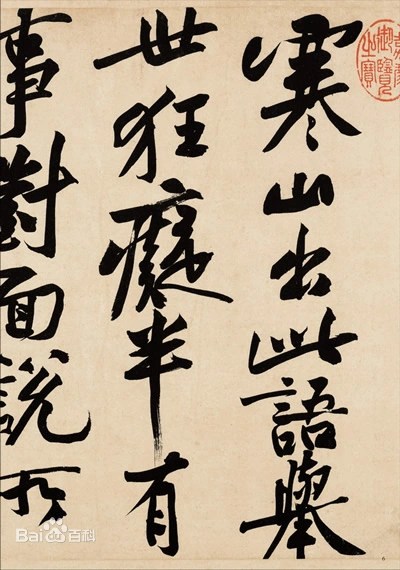

1.《鸟鸣涧》

鸟鸣涧

人闲桂花落,

夜静青山空。

月出惊山鸟,

时鸣春涧中。

Birds Calling in the Ravine

With people at leisure, osmanthus blossoms fall;

In the still night, green mountains lie empty.

When the moon rises, it startles the mountain birds,

Who now and then cry out in the spring ravine.

Commentary

In the first two lines, the poem’s focus settles on the words “fall” and “empty.” “Fall” portrays the poet’s unhurried, leisurely state of mind—only then can one sense the tiny osmanthus blossoms drifting down without a sound. “Empty” depicts the vast, far-reaching atmosphere created by the stillness of night.

The next two lines shift from silence to sound: “startled” and “crying” further express the tranquility of the moonlit night and the emptiness of the valleys. The most interesting point is that through the birds’ cry, the desolate quiet of the first lines suddenly gives rise to a pulse of life, filling the poem with vitality amidst its serenity. This is precisely the elegant, leisurely attitude toward life that Wáng Wéi pursued.

2.《杂诗》

君自故乡来,应知故乡事。

来日绮窗前,寒梅着花未?

Miscellaneous Poem

You come from my old hometown—

You must know the affairs of home.

Tell me, before the embroidered window,

Has the winter plum begun to bloom?

Commentary

This is a uniquely conceived poem of homesickness. The poet expresses intense longing for home through concern for the plum blossoms there. All four lines are the traveler’s questions—implying deep care for his homeland.

He could ask about many things, yet he chooses the plum outside the window. This seemingly small and casual question contains boundless longing and affection. The “winter plum” is no longer just a plant before the window, but a symbol of all that is worth remembering at home—an embodiment of homesickness that feels intimate, natural, and full of meaning.

3.《相思》

红豆生南国,春来发几枝。

愿君多采撷,此物最相思。

Longing

Red berries grow in the southern land—

In spring, how many new branches appear?

I hope you gather them in plenty,

For this is the seed of deepest longing.

Commentary

This poem was written for the famous singer Li Guinian. In only twenty characters, it expresses the poet’s heartfelt affection. After the An Lushan Rebellion, Li Guinian wandered in the south, and it is said he often sang this poem, deeply moving all who heard it.

The first two lines naturally and sincerely introduce the red berries. The last two lines convey feeling through metaphor—intimate and touching. Centered entirely on the symbol of the red berry, the poem expresses longing with simplicity and warmth, creating a lasting emotional resonance.

4.《九月九日忆山东兄弟》

独在异乡为异客,每逢佳节倍思亲。

遥知兄弟登高处,遍插茱萸少一人。

Thinking of My Brothers on the Double Ninth

Alone in a strange land as a lonely guest,

Every festive day my thoughts of home double.

From afar I know my brothers have climbed the heights;

Among the dogwood sprigs they wear, one person is missing—me.

Commentary

This is a festival poem expressing longing for family.

The first two lines describe the poet’s inner feelings during the festival. In the first line, one “alone” and two uses of “foreign/strange” portray a deep sense of isolation and unfamiliarity, making the second line’s “doubled homesickness” especially affecting. It resonates with anyone who has spent a holiday far from home, touching the heart and becoming a timeless line.

The last two lines use the custom of climbing heights and wearing dogwood on the Double Ninth Festival to imagine the poet’s brothers back home. This not only shows his longing for family but also emphasizes his own disappointment and loneliness—deepening the poem’s theme.

5.《渭城曲》 / 《送元二使安西》

渭城朝雨浥轻尘,客舍青青柳色新。

劝君更尽一杯酒,西出阳关无故人。

Song of Weicheng (also Seeing Yuan Er Off to Anxi)

Morning rain at Weicheng dampens the light dust;

At the travelers’ lodge, the willows look freshly green.

I urge you—drink one more cup of wine,

For once you pass west of Yang Gate, there will be no old friends.

Commentary

The poem depicts the emotional scene of parting with a close friend. The first two lines describe the beauty of the homeland after rain; the last two express the affection and reluctance at parting.

Artistically, the opening lines serve as a gentle prelude, while the final lines reveal the true theme. The poet skillfully conveys sorrow and tenderness with restraint, making the emotions sincere and warm. Thus this poem has been passed down through the ages and is loved by generations.