Case Studies of Yì Jùsūn 易巨荪

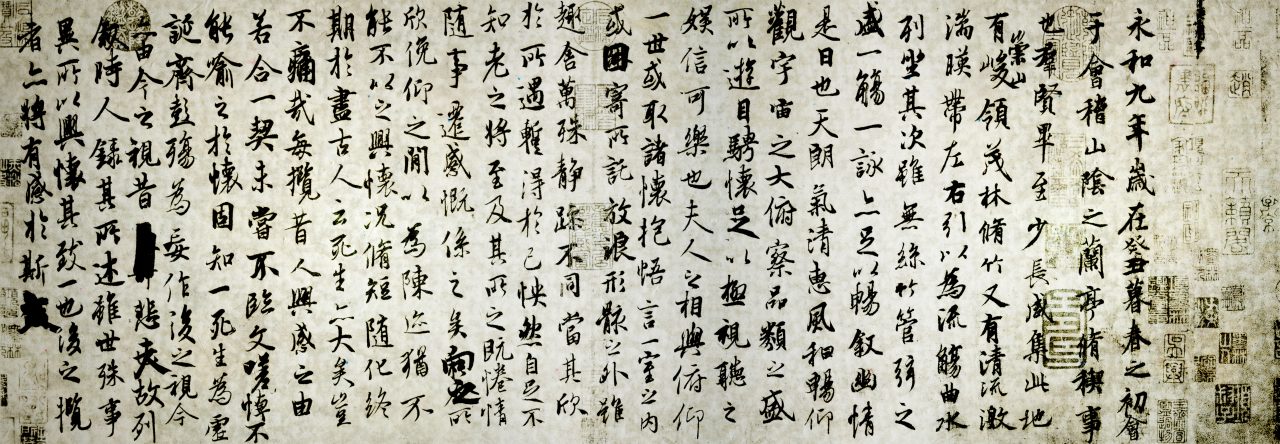

From ‘Case Studies from Collective Insight’ 集思医案

Introduction

Late Qing medical literature is often remembered through the works of prominent theorists and canonical editors, yet much of classical Chinese medicine was preserved and transmitted through the lived experience of working clinicians. Yì Jùsūn 易巨荪 belongs firmly to this latter group. Active in the late Qing period and practicing primarily in the Yuè 粤 (Guangdong) region, Yì was not a court physician nor a system-builder, but a physician whose legacy survives through detailed clinical case records. These cases provide a rare and valuable window into the day-to-day application of classical formulas in real clinical settings.

Yì Jùsūn’s medicine is unmistakably grounded in the Shānghán lùn tradition. His diagnostic reasoning consistently prioritizes concrete signs—pulse, abdominal findings, and the patient’s immediate presentation—over abstract theorization. Treatment follows the principle of formula–pattern correspondence (fāng zhèng xiāng yìng 方证相应), with classical formulas applied decisively and adjusted according to the evolving pattern.

Throughout his cases, Yì demonstrates a willingness to employ strong attacking methods when indicated, including in postpartum conditions, directly challenging later doctrinal assumptions that such presentations must always be treated as deficiency.

Stylistically, Yì’s writing is direct and pragmatic. He frequently critiques prevailing medical habits—such as rigid seasonal explanations of disease or formula selection based on theoretical preference rather than presentation—and instead insists on reassessing the pattern as it unfolds. His cases illustrate dynamic transformations between yīn and yáng, interior and exterior, and excess and deficiency, embodying the flexible, moment-to-moment clinical reasoning central to classical Shānghán medicine.

Although Yì Jùsūn never achieved the renown of figures such as Kē Qín柯琴, his work reflects the same clinical spirit that later informed the modern jīngfāng 经方 revival. Preserved largely in regional compilations rather than widely circulated standalone texts, his writings have remained relatively obscure. Yet precisely because of this, they retain a raw clinical clarity, offering contemporary readers insight into how classical medicine functioned outside the academy and beyond rigid doctrinal frameworks. Revisiting Yì Jùsūn’s cases today allows us to reconnect with a lineage of practice that is concrete, responsive, and deeply rooted in classical clinical reality.

Case Studies

【一】福建谢宽,寄居粤城,癸未三月,其妻患腹痛,杂药乱投,月余不效。延余诊视,六脉滞涩,少腹满痛,拒按,大小便流通。断为瘀血作痛。投以桃仁承气汤,二服痊愈。盖拒按本属实症,大便通,知不关燥屎,小便通知非蓄水,其为瘀血无疑。

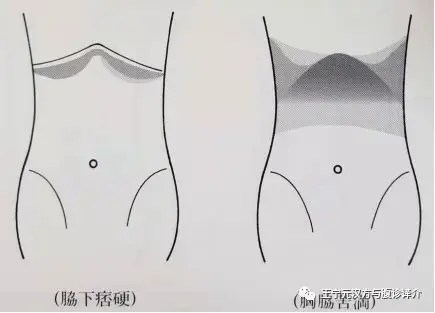

[1] Xiè Kuān 謝寬 of Fújiàn 福建, residing temporarily in Yuèchéng 粤城. In the third month of the guǐwèi 癸未 year, his wife suffered from abdominal pain. Various miscellaneous medicinals were administered indiscriminately; after more than a month there was no effect. I was invited to examine her. The six pulses were stagnant and rough; there was fullness and pain in the lesser abdomen, with resistance to pressure; urination and defecation were unobstructed. I judged the pain to be caused by static blood. Táorén Chéng Qì Tāng 桃仁承气汤 was prescribed; after two doses she was cured. Resistance to pressure fundamentally belongs to an excess pattern. With the stools free, it was known not to involve dry feces; with urination free, it was known not to be water accumulation. That it was static blood was beyond doubt.

【二】河南永发店,予先人旧日所做生理也。癸未六月,有店伴陈姓者,其妻患产难,二日始生,血下甚少,腹大如故,小便甚难,大渴。医以生化汤投之,腹满甚,且四肢头面肿。延予诊视。不呕不利,饮食如常,舌红黄,脉滑有力,断为水与血结在血室。投以大黄甘遂汤。先下黄水,次下血块而愈。主家初亦疑此方过峻。予曰:”小便难知其停水,生产血少知其蓄瘀,不呕不利,饮食如常,脉有力知其正气未虚,故可攻之。若泥胎前责实,产后责虚之说,延迟观望,正气即伤,虽欲攻之不能矣。”主家坚信之,故获效。

[2] Yǒngfādiàn 永发店 in Hénán 河南 was a place where my late father formerly engaged in livelihood. In the sixth month of the guǐwèi 癸未 year, there was a shop companion surnamed Chén 陈, whose wife suffered from difficult childbirth. The child was delivered only after two days; the blood discharged was very scant, the abdomen remained as distended as before, urination was extremely difficult, and there was great thirst. A physician administered Shēng Huà Tāng 生化汤. The abdominal fullness became severe, and moreover the four limbs, head, and face became swollen. I was invited to examine her. There was no vomiting and no diarrhea; appetite was normal; the tongue was red with yellow coating; the pulse was slippery and forceful. I judged this to be water and blood binding together in the blood chamber (xuè shì 血室). Dàhuáng Gānsuì Tāng 大黄甘遂汤 was prescribed. First yellow water was discharged, then blood clots were expelled, and she recovered. The family at first also doubted that this formula was too drastic. I said: “Difficulty in urination indicates retained water; scant bleeding after delivery indicates stored stasis. With no vomiting or diarrhea and normal appetite, and with a forceful pulse, it is known that the upright qì has not yet become deficient; therefore it can be attacked. If one rigidly adheres to the saying that before delivery one treats excess and after delivery one treats deficiency, and delays while observing, the upright qì will then be damaged, and even if one wished to attack, it would no longer be possible.” The family firmly trusted this, and thus efficacy was obtained.

【三】甲申六月,木匠李某亦在永发店出入。其妻患发热恶寒,不药自愈。转而腹痛,渴欲饮水,水入则吐,大小便不通。予曰:”脾不转输,故腹满痛,不输于上渴饮而吐,不输于下故二便不通,法宜转输脾土。”投以五苓散,一服痊愈。

[3] In the sixth month of the jiǎshēn 甲申 year, a carpenter surnamed Lǐ 李 also frequented Yǒngfādiàn 永发店. His wife suffered from fever and aversion to cold; without medicinals she recovered on her own. Subsequently she developed abdominal pain, thirst with desire to drink water, vomiting upon intake of water, and obstruction of both urination and defecation. I said: “The spleen fails to transport and transform; therefore there is abdominal fullness and pain. Not transporting upward, there is thirst with drinking and vomiting; not transporting downward, therefore the two excretions are obstructed. The method should be to restore the transport of the spleen earth.” Wǔ Líng Sǎn 五苓散 was prescribed; after one dose she was cured.

【四】甲申十月,西关锦龙南机房潘某之妻,少腹痛,每腹痛甚则脉上跳动,气上冲不竭,息苦楚异常,月余不效。予断为奔豚。投以桂枝加桂汤一服,茯苓桂枝甘草大枣汤一服,痊愈。

[4] In the tenth month of the jiǎshēn 甲申 year, the wife of Pān 某, from the southern weaving workshop of Jǐnlóng 锦龙 in Xīguān 西关, suffered from pain in the lesser abdomen. Whenever the pain became severe, the pulse leapt upward, qì surged upward incessantly, and breathing was extremely distressed. After more than a month there was no effect. I judged this to be bēn tún 奔豚 [running piglet]. One dose of Guìzhī Jiā Guì Tāng 桂枝加桂汤 was given, followed by one dose of Fúlíng Guìzhī Gāncǎo Dàzǎo Tāng 茯苓桂枝甘草大枣汤, and she was cured.

【五】乙酉四月,南海李总戎斌扬之妻患头痛。每痛则头中隐隐有声,即有血从鼻中流出,精神颓,肌肉瘦。诸医川祛风活血之药,愈治愈其。延予诊视,适座中有一老医,谓其脑下陷,例在不治。予笑而不答,许以十五日愈。病家未之深信。然素慕贱名,亦姑试之也。予用大剂当归补血汤加鹿茸数两,如期而愈。盖督脉从腰上头入鼻,又主衄血,故重加鹿茸以治督脉,不似他方之泛泛,故奏效也。

[5] In the fourth month of the yǐyǒu 乙酉 year, Bīn Yáng, the wife of Lǐ Zǒngróng of Nánhǎi suffered from headaches. Whenever the pain occurred, there was a faint sound within the head, followed by bleeding from the nose. Her spirit was dejected and her flesh emaciated. Various physicians administered medicinals to dispel wind and invigorate blood, yet the more she was treated, the worse she became. I was invited to examine her. It so happened that an elderly physician was present, who said that her brain had sunken downward and that this condition was, by precedent, incurable. I smiled and did not reply, but promised recovery within fifteen days. The family did not deeply believe this. However, having long admired my humble reputation, they tentatively tried it. I used a large dosage of Dāngguī Bǔ Xuè Tāng 当归补血汤, adding several liǎng of Lùróng. She recovered as promised. The Dū Mài runs from the waist up to the head and enters the nose, and it also governs epistaxis; therefore Lùróng was heavily added to treat the Dū Mài. This was unlike other formulas applied indiscriminately, and thus efficacy was achieved.

【六】乙酉夏,吾粤霍乱盛行,从阳化者热多,口苦渴,舌红,古法川五苓散,粤人用纯阳仙方多效。然入阴者死,出阳者生。阳症其轻,亦有不药自愈者。惟从阴化之症寒多,不欲饮,即饮亦喜热水,古法用理中汤,且有吐利一刻紧一刻,手足冷,声嘶日陷或手足拘急,复大汗出则死矣。古人嫌理中力薄用通脉四逆汤或四逆汤。予遂其法治之。附子有用至二两,干姜有用至两以上者。全活甚多,但此症内霍乱外伤寒,从阴从阳瞬息不同用药亦当(如转圈)。营长李某,上吐下利,恶寒,盛暑亦覆被,面目青,昏不知人。延予诊视,断为阴症。甫订方,即闻病者呻吟,自发去衣被,恶寒转而恶热,面青转而面赤,吐利亦渐止。予为之贺喜曰:”病已由阴出阳,自内而外,为将愈之兆。拟桂枝汤一服全愈。(凌波按:今日此等热症颇多,往往视而畏寒、口渴,处方甫毕转为恶热口渴。走马看伤寒,信不我诬。)

[6] In the summer of the yǐyǒu 乙酉 year, cholera (huòluàn 霍乱) was rampant in our Yuè 粤 region. Those transforming from yáng were mostly heat patterns, with bitter mouth and thirst, red tongue; according to ancient methods Wǔ Líng Sǎn 五苓散 was used, and among the Yuè people, the use of purely yáng “Immortal formulas” was often effective. Yet those entering yīn died, and those emerging into yáng lived. Yáng patterns were relatively mild, and some even recovered without medicinals. Only the patterns transforming from yīn had much cold, no desire to drink; even when drinking, they preferred hot water. According to ancient methods Lǐ Zhōng Tāng 理中汤 was used. In some cases vomiting and diarrhea alternated in urgency, the hands and feet were cold, the voice hoarse and daily sinking, or the hands and feet were clenched; if copious sweating then occurred, death followed. The ancients considered Lǐ Zhōng Tāng insufficient in strength and used Tōng Mài Sì Nì Tāng 通脉四逆汤 or Sì Nì Tāng 四逆汤. I accordingly followed this method in treatment. Fùzǐ 附子 was sometimes used up to two liǎng, gānjiāng 干姜 sometimes exceeding one liǎng. Many lives were fully saved. However, this pattern is internally cholera and externally cold damage 伤寒; transformation from yīn or yáng can change in an instant, and medication must also change accordingly (like turning a wheel).

A battalion commander surnamed Lǐ 李 had profuse vomiting and diarrhea, aversion to cold, and even in the height of summer covered himself with quilts. His face was bluish, and he was unconscious. I was invited to examine him and judged it to be a yīn pattern. Just as the formula was being decided, I heard the patient groan; he spontaneously removed his clothing and bedding, aversion to cold turned into aversion to heat, the bluish complexion turned red, and the vomiting and diarrhea gradually ceased. I congratulated him, saying: “The disease has already emerged from yīn into yáng, moving from interior to exterior—this is a sign of impending recovery.” One dose of Guìzhī Tāng 桂枝汤 was prescribed, and he fully recovered.

(Líng Bō 凌波 notes: Today such heat patterns are quite common. Often they present with aversion to cold and thirst; just as the prescription is completed, they turn into aversion to heat with thirst. To observe cold damage as if galloping on horseback—this saying does not deceive.)